La Mano

Sergio De Loof – Miramar’s Time

No. 74 – Buenos Aires, May 2010

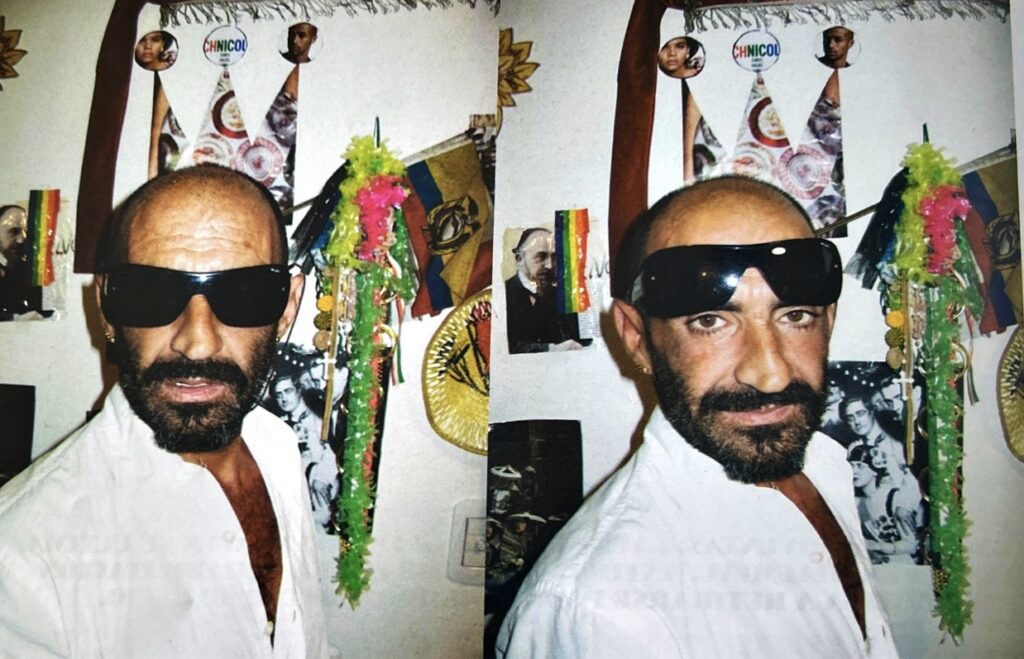

Nineties icon. Laura Batkis interviewed him during his last exhibition at Miaumiau, before going into a rehabilitation program that forces him to stay away and be silent for a while.

He was the mentor of El Dorado, nightclub that brought together all of those who came out of the closet during those years when there was an air of renewed freedom. He also created Morocco, Poodle and Ave Porco, until AIDS suddenly barged in and put an end to the party. In the gastronomy field, he created El Diamante and Pipi Cucu. And he was part of the editorial team of Wipe magazine. He is a complete artist, who goes from painting to photography, including fashion, decoration and shops décor.

Laura Batkis: Tell me about Miramar, the exhibition.

Sergio De Loof: I have been going to Miramar since I was born. It is elegant, but for some years it has not had good press, Pinamar with P beat it, and Cariló. Miramar suffered a downturn in the press but I think it was and is a very elegant city. It has everything that is happening to the cities, which are the printed signs… did you see that they print all the signs? They don’t leave them in metal, they change them for prints. Now in towns they cover everything in printed vinyl, there are no people directing the aesthetics of the cities with preservation criteria.

What is your personal relationship with that place?

Miramar was my childhood city and it was very elegant. It was very fifties. I was a teenager, I rode my bike, I went to private parties that didn’t let you in if you weren’t a cheto (a high class person) or a friend of I don’t know what family.

The life of a teenager. There was a soda shop called Mickey’s that sold milk shakes, and now it’s turned into the same thing, but without the soda fountain. It was a life, I had a life. For me the best parts of my family are the years gone by. I was born in ’62, my parents were very refined even before I was born. My mom had real pearls. We were high middle class and now we are lower middle class. And I don’t know how many people it happened to or why it happened to them, if they came down because of depression, if it was the country or the governments. We had a beautiful country house in Remedios de Escalada, our house in Miramar and my house in Banfield where I used to play tennis. Now we ended up in a much poorer neighborhood, in Hudson Berazategui. We were an elegant and well positioned family. My father is an industrial chemist, my mother is a housewife, she never needed to work, with my father’s money everything was fine. My mother’s name is Snow White, and she wrote the prologue of this exhibition. My brothers are university students. I insist, everything was fine, I don’t understand this class decline, this change of class that happened to us. We are living with the poor when we were not so poor.

There is some nostalgia in this exhibition, that family history from your teen years where you lived well.

Yes, totally. Our house in Miramar is still there, we didn’t sell it. It is the last thing that remains of my family’s splendor, of my family’s good times, of the fifties and sixties.

It was a time when I was happy, I had no complexes, I didn’t compare myself to anyone, everything was fine.

And you stopped being happy at a moment…

Yes, very much so.

Do you remember when that happened?

Look, I remember a story about a Jewish friend of mine who had a sound system that I didn’t have at home, so I went home and told my mother, “Mom, there are people richer than us”. And she answered “Yes son”.

That happened in high school. I didn’t know that people had more money than others.

I stopped being happy… let me think… from ‘91 to ‘95 I had El Dorado, El Morocco, Caniche, Ave Porco… I was very happy, I had the best places in Buenos Aires. Everything was mine. I was… I don’t know who I was, but I had decorated them. That ended when I was diagnosed with HIV almost 14 years ago and I had to figure out what to do with my profession and my disease. How I was dealing with it.

Many artists of the 90s started with the diagnosis of HIV: Kuropatwa, Feliciano Centurión, Omar Schirilo, Juan Calcarami, Liliana Maresca… and some marchands such as Alejandro Furlong.

Yes, for me nightclubs are over. Even though Club 69 exists, for me it is brainless, the world changed with HIV, even though there are still parties. It was a plague that I don’t understand… Juan Calcarami, who died, used to say that someone put it in us to ruin our lives, as if they put a virus in us so that we would stop being happy. That changed everything. Now a nightclub, what for?

Now, you can only have sex with someone who is very safe, it’s all a paranoia, so why put a nightclub if nightclubs are designed to end up having sex? Sex is so dangerous that it’s not worth having a nightclub.

Then came restaurants like El Diamante….

My AIDS numbers were so good, regarding the amount of HIV in my blood, that they suggested not to take any more medicine because I was splendid, as if I had been cured. It was then that I started El Diamante and it meant returning to night life. I spent six years without taking medication. Now I am in bad health, HIV has advanced and what happens is that it is difficult for me to take medication again, because I have to leave the nightclub environment again. Psychologists do not understand that in this environment you must be high. In one way or another. Self-esteem is not something you are born with; you need a crutch.

Now they take that crutch away from you.

Of course, so I have to leave, because it could happen that I have nothing to talk about. Like Charly García who, for me, should retire from the show business if he has money because he is a depressing fat man. He is not Charly.

I don’t want to be a fat Sergio De Loof giving shows.

This would be an exhibition before retirement.

Yes, I’m going into rehab. Alcohol and cocaine. Only alcohol relaxes my stomach, otherwise I am never hungry.

And since I need money for rehab I made this exhibition, and with what was sold I pay for the first month. It’s all so incredible, I was a very avant-garde person, I invented so many things, that for me… it’s so easy for me to do art… that sometimes I think that art is a con, because things come to me that way, easy. But at the same time this happens… this pain and everything that happens to me. I am suffering. I’m suffering, because I was fired from my last restaurant I owned, I was fired by the partners of Pipi Cucu, and also from Wipe magazine.

Why did they kick you out?

Because I am a very intense person.

It seems that nowadays intensity is taken as a disease.

Yes, and there is a lot of jealousy. They can’t stand how easy it is for me, it comes naturally to me. Because for me life and art are the same thing, thank God.

God gave me a gift and others hate it instead of loving me, they are jealous of me.

Can you imagine a comeback after this retreat?

I don’t know. I think I’m going to go back to drinking because I love it, I’m like Cacho Castaña, cigarettes and whisky. For a while I’m going to take care of myself to recover my defenses. I can’t imagine being an Ayurvedic. I can’t imagine De Loof without whisky and cigarettes. Not yet.

There is a piece in this exhibition that is the photographic documentation of the destruction of some paintings. Why did you burn them?

With the money I had left from the Porto Alegre Biennial, in November I went to Miramar. I took oil paintings and frames to paint pictures for this exhibition. I started painting. I think there are times when you have bad luck, when God sets things in your way in order to make you fall. They tell me that it is because I drink alcohol that I fall, but apart from that God puts a banana in front of me to make me fall, and he wants me to suffer so that I learn something. I say this with total mental clarity. Many things happened to me with these oil paintings, for example, I put the oil painting and it got full of mosquitoes or it rained, everything happened to me. I made a mistake with the material, I wanted to paint the umbrella but it had to be in acrylic. For three months I had to leave the room where the paintings were because I couldn’t sleep. I know what the environment is like, what people think, what is right, what is wrong… the mamarrachada (nonsense). And I knew that what I was doing was not right. It was a downer, I couldn’t face that. I couldn’t stand here with pride and dignity knowing that I had done a bad show, there were mosquitoes and I don’t know how to handle oil. So I decided to burn everything. I called Mariano from the Miaumiau gallery and said no to oil paintings because they were horrible. I said let’s either suspend the show or take pictures instead. So I took photographs and they are all sold.

There is also an installation on the wall at the entrance of the gallery, which is like an accumulation of things: magazines, tapes, everything. And it’s sold. How does the person who buys it hang it?

Yes, it was bought by a lovely guy, who seems to have come and bought almost the whole exhibition. As always, I go and put it together at the collector’s house, so I’m happy because I’ll be able to visit him at home.

BY LAURA BATKIS