Lapiz

Analía Segal

ICI. Spain Cultural Center (Buenos Aires). No. 176 – October 2001

At the Spain Cultural Center (ICI) you can visit the exhibition of Analía Segal. Born in Rosario, Argentina in 1967, she moved to Buenos Aires eleven years later. Starting from then, she began her eclectic education, which led her to develop her artistic career and her profession as a designer at the same time. While working as an assistant in the studio of sculptor Jorge Michel, she began her career in graphic design at the University of Buenos Aires. In 1989 she left for Florence and Pietrasanta, thanks to a scholarship granted by the Cleveland Institute of Art. During the year she spent in Italy, she progressively developed her alliance with sculpture, learning to handle marble, wood and bronze casting. In Buenos Aires, she was part of the first group of scholarship holders of the Taller de Barracas, sponsored by the Fundación Antorchas under the supervision of Luis Benedit and Pablo Suárez. In 1999 she went to New York University to pursue her master’s degree. Since then, she has remained in the United States.

The change of country was crucial in her creative process. From the sensation produced in those tiny Manhattan apartments, with the constant moving of its inhabitants, came the possibility of transforming that experience of claustrophobia into a material act. So she began to punch holes in the walls. Almost without knowing it, this would be the key to her current artistic production: wall interventions.

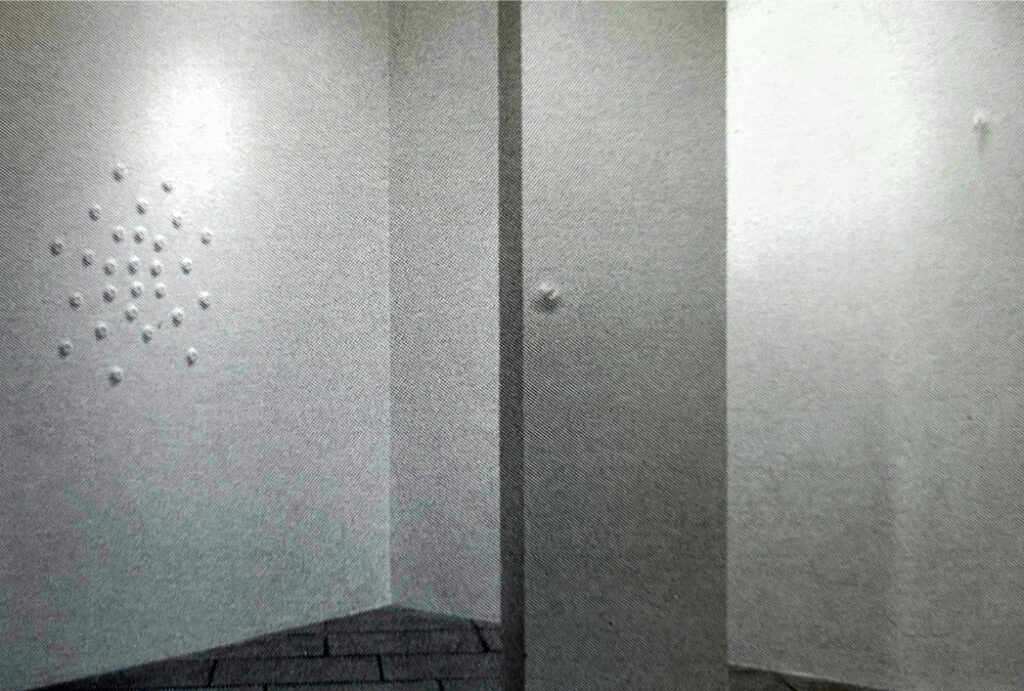

Since she works based on the assigned space, it is a “site related” artwork, since the speculations about the possibility of transformation arise in absolute relation to the type of wall of the site in which the artist creates at any given moment. Therefore, the architectural space is fundamental in the development of the whole installation. Before coming to Argentina for this exhibition, she presented Aldous, an installation at the Islip Art Museum in Long Island. On that occasion she was dealing with a place that had functioned as a carriage house. The challenge, therefore, was to dialogue with the pregancy of a wall made of wooden slats. Thus, she placed her small objects, altering the morphology of the place, which now looked like a musical pentagram. In a similar way, Roman, exhibited at the New York University gallery, presented her with a very particular site: the angle of a wall.

What for others is a difficulty, for Segal is precisely the incentive to execute her installations.

For this exhibition at the ICI in Buenos Aires, the artist developed a project that she put together during her stay for the setting up of the installation. The piece consists of the intervention on the walls of small shapes that she has previously elaborated. Each piece, separately, is like a miniature in polished plaster that looks like a porcelain jewel. The shapes are always organic, like objects of desire that allude to bodily orifices, drips, grains and protuberances. The organic quality allows her to set up a game free of interpretation by the viewer, and avoid referring to the hermeticism of the geometric. All the elements have the potential for transformation, not only because of their form, but also because of the changing content they acquire when they are re-signified in different spaces. In this case we find two situations. On the one hand, the composition by placing the pieces in sets, which when seen give the sensation of a rash, as if the wall had suddenly been attacked by an allergic disease.

The concentration gives way to an isolated element that covers the entire frame of a wall. Thus, the reading moves through areas in which the excess of information transforms the environment into a nightmare, alternating with the pause of silence. The strategy consists of not altering the pre-existing space. To this end, Segal works carefully with each piece, painting it in the same color as the wall on which it is placed, so as not to change the recognizable aspect of the room.

In a diagram, located at the entrance of the gallery, a sort of dictionary points out the names of each of the shapes: Aldous, Henry, Anaïs, Gal, Eves and Vaune, among others. In this way, the work acquires a greater meaningful ambiguity. Names of her own, of people, films, friends or readings that belong to the artist’s private world. Therefore, these pieces inserted in the wall take on another dimension, as if the name were the guarantee of their existence. A personal lexicon that seems an attempt to rationalize the ineffable.

Like a science fiction capsule, the space is populated by microorganisms that alter the perception of the place. And, at the same time, they give the whole gallery a rare and provocative sensuality, turning the walls into surfaces of pleasure.

BY LAURA BATKIS