La Mano

Pablo Suárez – Art as a Tool Full of Future

No. 1 – Buenos Aires, April 2004.

Pablo Suárez put his gloves back on to step into the ring, and today he undertakes his battle against indifference, the most powerful invisible enemy that is encircling the daily life of Argentines.

In addition, with his artworks he continues to present us with the urgent need to recover the meaning of art and life.

A couple of weeks ago, Pablo Suarez crossed the pond to bring back a series of sculptures he made in his workshop in Cologne, where he currently lives, and put together a new solo show at Maman Fine Art, something he has not done since 2000.

It is surprising that the character of the boxer is almost a prototype in your production.

Boxing is a miserable profession, it’s almost not a sport! Whoever steps into a ring already knows beforehand that physical and mental deterioration is an inevitable consequence. And he climbs because he has to survive. On the other hand, when people die young it is said that, “He didn’t even have time to cast a shadow on the ground.” These are popular phrases that I like.

You show a wild world.

After so many years of talking about freedom, equality and fraternity, we are still like animals in a more or less sophisticated fight, but a fight to the death in order to survive. The poor person who used to eat soup is now an ingredient in the soup of a stronger predator: he is an ingredient of the rich. This is how the world is designed, in a bad way of course, but it is inevitable, and I would like to believe that this can be reversed, for it not to be like this.

If I took the Suárez card and place it in the “political art” category, would I be right?

No, I don’t do political art, never. I make social art; I talk about society. From what I see and live, I draw conclusions and make art. Besides, I am not a fundamentalist. The world changes and so does my perception of the world, because it also changes me. I point without judging. The artist cannot be a kind of supreme judge. I feel closer to the place of my representations than to the place of the courtroom, and as unprotected as the characters in my works.

Why don’t people understand contemporary art?

It’s good that they don’t understand it because contemporary art is an experimental art, and experiments are made by those who are dedicated to making experiments. Luckily there are artists whose work escapes experimentation and is installed in the world as a necessity of the author and as a new order. The problem comes when you repeat the same experiment that was done in the 40s, 50s and 60s … and forty years later you do it again in the same way, almost without any variation, so should we still call it an experiment? If a new conclusion were to be drawn, maybe. But to keep repeating it just for the sake of experimenting doesn’t make sense. And that’s what I see in much of the art academy today, the only thing I see is the past.

Don’t you think that the art critic who is pressured every week to write a piece is as victimized by this corporate system as the artist who has a full schedule of art shows, fairs and biennials?

Yes, absolutely. It starts to become a job like any other.

Do you think that the critic legitimizes the work of art?

At first glance, yes. But in general, the critic arrives to an artist’s production once it has already been endorsed by other colleagues. It is actually the artists who legitimize the work of other artists.

Is there more intermediation than before?

Much more. You must have good contacts, have well-made folders to sweeten the meeting with anyone, in any corner, because you know that everyone walks around with a book under their arm. Fortunately, there are other ways, like Sebastián Gordín, who, thanks to the respect of his colleagues, is slowly finding a space in the public opinion. And I am glad about this. It will have taken him longer, it must have been harder for him because he does not have a media predisposition. But when you see that the work of an artist not only remains (I am referring to his last exhibition, Pequeños reinos, at the Fundación Telefónica), but that it develops in front of your eyes, you feel, as very rarely, a strange emotion when you see that he creates that from a vital experience and nothing else. For me, that is the example of the artist who was not a sprinter.

There is talk of a resurgence of art after the crisis.

I don’t know if it was because of the crisis or not, but there was a growing mobility in the art world. New spaces were created, such as Belleza y Felicidad, Sonoridad Amarilla. It is likely that in the face of the general depression, people’s response was to generate things. A French sociologist – I don’t remember the name – was astonished by the Argentine phenomenon. This permanent sizzle of artistic activities anywhere in the city, in unusual places like in a butcher’s shop. He said that it is impressive that in an economically bankrupt country there is more cultural activity than in France, which has a huge budget for culture. An encouragement and a passion for creation that overflows critical judgment. And the phenomenon of renowned artists who also move through alternative spaces supporting the emergence of this effervescence. It corresponded to the awareness of the horror that had occurred and which had never been talked about. The horror of Menemism and all that it brought about.

Describe this proximate horror.

Menemism produced the impoverishment of the country in a shameful way. Supported by international groups of very strong economic power, the country was handed over, pretending that it was being sold. We are now in a period in which they are trying to somehow recover the strings to manage this country that had become a country handed over in the most corrupt way. I believe that this boom in corruption has never been experienced before. To the point that it demoralized even the cleanest people. It has morally perverted the people, which is even worse than having defrauded them economically. There was a betrayal of everything that had been previously said in the campaign, and of a government that called itself “Peronist”.

You were a Peronist.

Yes, and now I feel Peronist again, or Justicialist, which is a broader term that includes the idea of social justice.

Could you describe that Pablo Suárez who was fascinated by Perón’s figure?

[He lights up as if longing for a distant past] Look, let me tell you. At the time of the first Perón a very large sector of society had obtained social identity, which was theirs to begin with. They had always been treated as if they were “nothing” and were incorporated into a social mechanism. That alone turned me affectively and rationally in that sense. Although Perón could have been arbitrary and politically dubious in some things, on the other hand, it must be recognized that he recovered sectors that could not even be said to have disappeared, because they had never even been considered.Is it possible to speak of a Peronist art?

No, not at all. I think there may be an art linked more or less to certain national issues, but to say Peronist art seems like nonsense to me.

However, such distinctions are often made.

Let’s take a case in point, Antonio Berni. He was a communist, so what? He was an artist, his social stance is reflected in the obvious anecdotal elements, but that is not what makes him a great painter. Because if we take only the subject matter we fall into the joke of some painters of socialist realism of the worst period. No. I am against impositions.

Is culture a field of resistance?

It should be. Imposing a trend is an unacceptable intrusion for the artist. They can’t force the models within which you can be more or less successful on you. You have to choose your possibilities and your path to follow, whether you like it or not.

Today artistic value is measured in terms of success or failure.

Because culture has been invaded by sponsors. And this sets conditions.

But there has always been patronage in art…

The problem is that the sponsor that appears with the logo in the catalog is not making a sacrifice. He uses art rather to launder taxes, and to give himself visibility by doing something to avoid going to the tax office and paying. And it also serves as an advertising campaign. Sometimes countries are sponsors. The case of Holland. They send curators to Latin America, give them scholarships, and only select those artists who work according to the mechanisms they have learned, those who have been culturally colonized. And when those artists come back, they tend to spoil.

If I didn’t know your work, and I wanted to see your current exhibition, how would you help me get closer to your world?

Through the title. The scarce margin is like an entrance door that refers to the situations that all sculptures pose. It portrays a social space. There is a part of society that moves like ants: nobody can individualize them, they are not stars, they are not in sight and practically go unnoticed. I am talking about today’s world, a world of needs and obscurity. That scarce margin where survival is already a success. I am talking about the smallest effort to get out of bed, to get to eat, to pay the light bills and things like that. What changed is the margin of begging, the whole society was approaching the most desperate pauperism. Homenaje al Bendigo (Homage to the Beggar) is an emblematic piece. Those circus characters who go to the squares and stand like statues for a coin, or who walk along an edge as in Poca fe (Little Faith). It is like a failed circus, full of tricks to survive that seem to be taken from the picaresque. Attempts to escape from deterioration, while the others swarm like cockroaches.

Like Discépolo’s Cambalache.

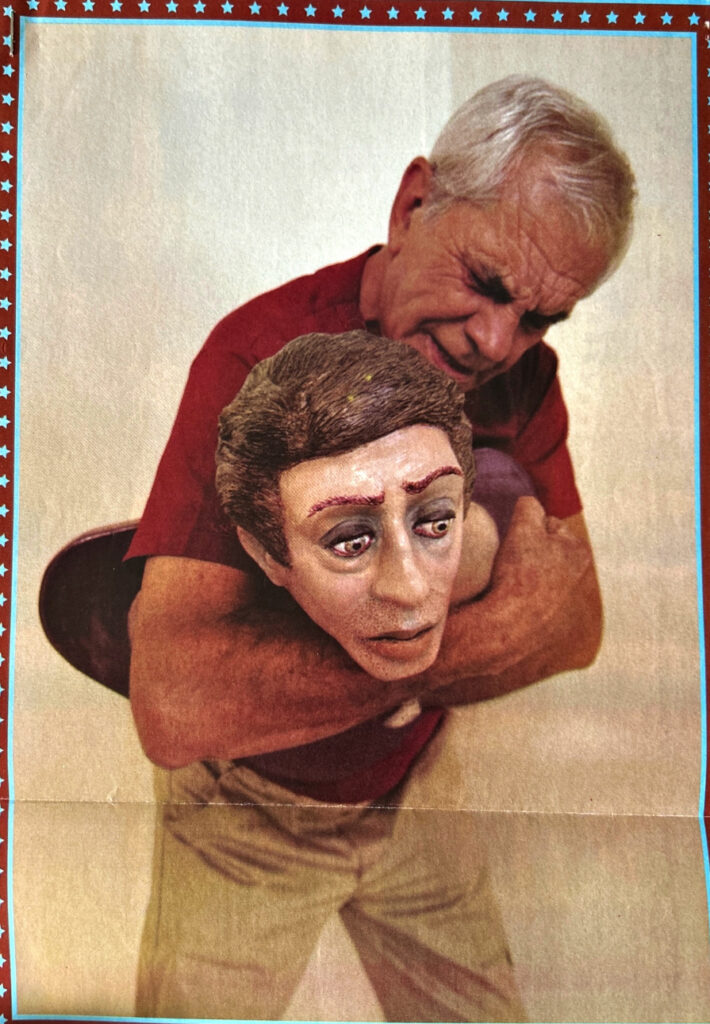

And ethical pauperization. That is why I included the Trofeos de guerra (War Trophies), which are human heads. Everything is presentable, it is part of the show. It seems to me that no one can generate such horror without ever making a mea culpa.

In Cazadores mediáticos (Media hunters) you refer to the fact that reality is only what happens on television.

Yes, snakes no longer have their natural environment to hunt their prey: they are happy to watch them on television. And yet, for me that scarce margin seems to be the most defining place in our society. It is more defining than that center which is a fiction. In this exhibition I want to show what I feel in regards to this situation. That kind of feeling you get when you walk through Plaza Constitución, but also the feeling you get when you talk to people who have lost most of their basic human expectations.

If only art critic Pierre Restany would listen to you! Do you remember when he came to Argentina in 1995? He left very angry about the lack of ideological commitment of the art of the ’90s, and said it was guarango (vulgar), like the government of the time, and started a debate that continues up to this day.

I don’t think that what Restany said was inappropriate. In the ’90s there was a voluntary silence on political issues, which I do not share. I think it is necessary for any person, artist or not, to express his opinion and take a risk. What happened is that in the art of the ’90s that opinion was not expressed verbally, I would say that there was a cautious attitude, but the artworks responded to a certain need of the moment.

There was talk of a “light” art, lightweight.

I don’t think that the work of the ’90s was more banal than previous expressionisms. In fact, it was brave enough to pretend to be so. But that is not the reality. The apparently hard ideological positions were always more banal, but then they were not maintained with actions.

Many were criticized, and even more so today, for this idea of not getting involved with social issues.

I would not criticize them at all. It is similar to what happened in the ’60s when the people of the La Paz bar criticized the Di Tella people for their lack of political commitment. And then it turned out that the Di Tella people were much more politically committed than the bar La Paz people.

How do you perceive the current art scene?

I see a kind of neo-conceptual academy all over the world, and in Argentina as well, neutral, it has no importance because it doesn’t even respond to the need of the times. There is a certain deafness.

Is art a job or a profession?

It is an activity that is based on what you feel, not on what you think. The visual arts are not so easily explained. You can try to set an academic reasoning for anything. Because the same theory that can support an informalist piece can support a brick on a wall. It is like the pyramid of the executives. Companies have more and more steps until they reach the one who really has the power. There are more and more steps, not only in art but in this globalized world of bureaucratic relations. People have to occupy positions that are absolutely unnecessary. Spokesperson, curator, press agent, communicator, the one who makes your image, and so on.

Do you feel in 2004 linked to the idea of the letter of resignation to Di Tella that you wrote in 1968?

I feel totally linked to that thought. The thing is that at the time of the letter I was making a cultural policy move. I saw a place where everyone’s speeches were being negotiated and annulled or perverted. What I did was try to point it out as a place that was losing sense.

It’s about being happy…

The pursuit of happiness is not about getting into a Jaguar. I’m more like a Jeep, or an SUV.

Who is Pablo Suarez?

Pablo Suarez began to exhibit his work encouraged by Germaine Derbecq. He did it individually for the first time in 1961 at the Lirolay Gallery in Buenos Aires. Since 1962 he worked with other artists such as Alberto Greco, Marta Minujín and Jorge de la Vega. In 1964 he exhibited his installation Muñecas bravas (Wild Dolls). He was part of the Di Tella group of artists since its beginnings, along with Santantonín, Renard, Delia Cancela-Pablo Mesejeán and Stoppani, among others. He worked together with Minujín in the creation of the installation La Menesunda (1965). He is connected to action art with performance linked to critical conceptualism, carried out in Experiencias ’68, when he presented his letter of resignation to Di Tella at the door of the Institute. Also in 1968 he participated in Tucumán Arde, along with Roberto Jacoby, Juan Pablo Renzi and León Ferrari, and others. Tucumán Arde was a political action operation, which showed the social situation in Tucumán. It was closed due to pressure from the government and the police. Between 1972 and 1973 he retired to San Luis, then lived in Córdoba. He adopted a realism, without avant-garde pretensions, following the painting of intimate Argentine artists such as Lacámera. He painted the series of Malvones, still lifes and desolate landscapes. During the 80’s his style was rooted in the grotesque and his painting acquired an expressionist tone. From the 90’s onwards he focused more intensely on parodic sculpture, taking social reality as the axis of his artistic speech. Today he is a figure of worship among the younger generations, both for his work and for his talks, opinions, conversations and debates on art.

Suárez’s famous resignation letter from the Di Tella Institute, 1968.

Letter handed out on Florida Street.

Mr. Jorge Romero Brest

A week ago I wrote you to let you know about the artwork I was planning to develop at the Di Tella Institute. Today, just a few days later, I feel unable to carry it through because of a moral impossibility. I still believe that it was useful, clarifying, and that it could have caused conflict with some of the invited artists, or at least questioned the concepts on which their works were based. What I no longer believe is that this is necessary. I ask myself: is it important to do something within the institution, even if it contributes to its destruction?

Things die when there are others to replace them. If we know the end, why insist on doing every last pirouette? Why not place ourselves in the limit position?

[…]It is clear that, by presenting moral situations in artworks, by using meaning as a medium, the need to create a useful language emerges. A living language and not a code for elites. A weapon has been invented. A weapon only becomes meaningful in action. In a shop front, it lacks all danger. I believe that the political and social situation of the country causes this change.Up to this moment I could discuss the activities developed by the Institute, accept them or judge them. Today what I do not accept is the Institute, which represents cultural centralization, institutionalization, the impossibility of valuing things at the moment in which they affect the environment. Because the Institution only admits already prestigious products that it uses when they have either lost their validity or are indisputable given the degree of professionalism of those who produce them, that is to say, it uses them without taking any risk. This centralization prevents the massive circulation of the experiences that artists can make. This centralization means that every product starts to feed the prestige, not of the person who created it, but of the Institute, which with this slight alteration justifies as its own the work of others and all the movement that it implies, without risking a single cent and still benefiting from the journalistic promotion.

If I were to carry out the artwork at the Institute, it would have a very limited audience of people who presume to be intellectuals by the mere geographical fact of standing quietly in the great hall of the art house. These people do not have the slightest concern for these things, so the legibility of the message that I could put forward in my work would be totally meaningless.

If it occurred to me to write VIVA LA REVOLUCION POPULAR in Spanish, English or Chinese, it would be absolutely the same thing. Everything is art.

[…] So? Then let those who want to climb work at the Institute. I do not assure you that you will get far. The Torcuato Di Tella Institute does not have the money to impose anything at an international level. Those who want to be understood in some way, say so in the street or where they will not be misrepresented. To those who want to look good with God and the Devil, I remind you that those who want to save their lives will lose them. To the viewers I assure you: what you are being shown is already old, second-hand merchandise. Nobody can give them manufactured and packaged what is happening at this moment: Man is happening, and the artwork: to design ways of life…(This resignation is an artwork for the Di Tella Institute. I think it clearly shows my conflict with the invitation, so I believe I have fulfilled the commitment).

BY LAURA BATKIS